EAT, DRINK & PLAY - GET OUT OF TOWN

Get Out of Town!

October, 2019 - Issue #181

|

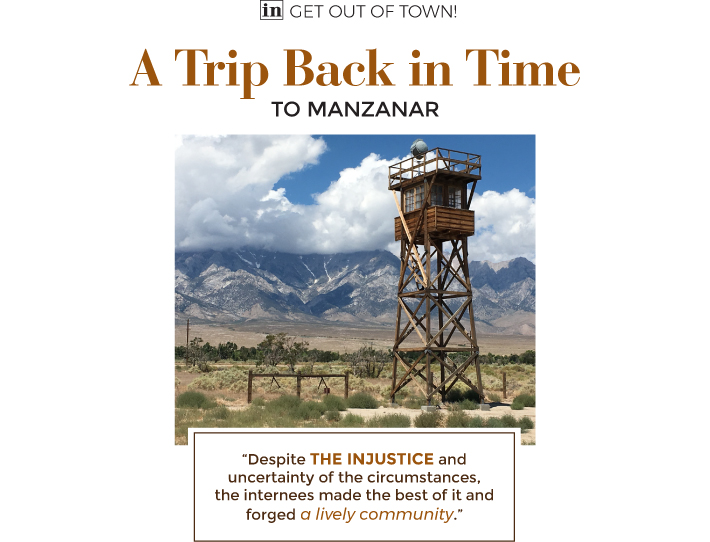

A stark, desolate beauty draws visitors to the Owens Valley. Its rugged isolation and proximity to the soaring granite peaks of the Eastern Sierra promise solitude hard to find elsewhere in California.

That iconic scenery also holds painful memories of a shameful blemish on our nation's history of liberty.

The Manzanar War Relocation Center opened just four months after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Fearing that Nisei - second-generation Japanese-Americans born in the US - and Issei, who immigrated from Japan - were collaborating with the Imperial Japanese military, the United States government ordered more than 110,000 residents of Japanese ancestry moved away from coastal areas and into one of 10 camps scattered around the US.

Today, Manzanar is a National Historic Site. Located just north of Independence off Highway 395, it sits in the literal and figurative shadow of nearby Mt. Whitney.

Reconstructed facilities and engaging exhibits explain how the camp came to be and help recreate daily life in a community of people forced together from disparate backgrounds.

A 3.2-mile driving tour follows the camp's perimeter. You're free to stop along the way, as Drew and I did, to explore the remains of building foundations, orchards, ponds and gardens. At the camp cemetery, an iconic obelisk inscribed with "Soul Consoling Tower" in Japanese keeps a lonely vigil in honor of those who lived in Manzanar and the few who died and are still buried there.

Manzanar held as many as 10,000 people between 1942 and 1945. Fishermen from San Pedro, businessowners from LA's Little Tokyo and farmers from Bainbridge Island, Washington - all forced from their homes and livelihoods with maybe a week's notice. Allowed to bring only what they could carry, families stepped off crowded buses and found themselves in what must have seemed the most desolate place imaginable.

A high desert valley hemmed by towering mountain ranges, the Owens Valley sees extremes in temperatures, "but always the wind," one internee recalled in the film "Remembering Manzanar" that plays in the visitor center.

Although the government sold most of the buildings after World War II, recreated facilities allow visitors to get a better feel for life at Manzanar.

The wind blew dust through the plank walls of the internees hastily-erected barracks, latrines and mess halls, all surrounded by barbed wire and watched over by guard towers that internees were told were there for their protection.

Each barracks building held four 20-foot by 25-foot "apartments," with as many as eight people sharing one apartment.

Standing in the summer sun on a dirt courtyard between a rebuilt mess hall and latrine, it's not hard for me to imagine how out of place the internees must have felt.

Inside the mess hall, a long counter anchors one end of the stuffy room. Here, cooks dished out what residents called "slop suey," which they ate at rough plank picnic tables.

With no running water in the barracks, common latrines - separate facilities for men and women - serviced each block of 14 barracks. The indignity is evident in the rows of partitionless toilets and communal shower room.

Despite the injustice and uncertainty of the circumstances, the internees made the best of it and forged a lively community. They beautified the otherwise stark surroundings with ponds and gardens, socialized at dances, organized sports leagues, and, if they had the means, ordered niceties from the Sears Catalog.

Reflecting on Manzanar, Miho Sumi Shiroishi said, "There is not much there anymore in the way of structures ... but a lot of memories remain."

Those memories will fade with the passing of the World War II generation, but Manzanar holds lessons for those willing to stop and learn them.

Eric Harnish lives in Castaic.

Visiting Manzanar

nps.gov/manz

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||